Graduate spotlight: Bio-artist and sculptor, Georgie Gerrard.

Continuing with our showcase of place-based making, we chatted to Georgie Gerrard - a textiles graduate from Loughborough University.

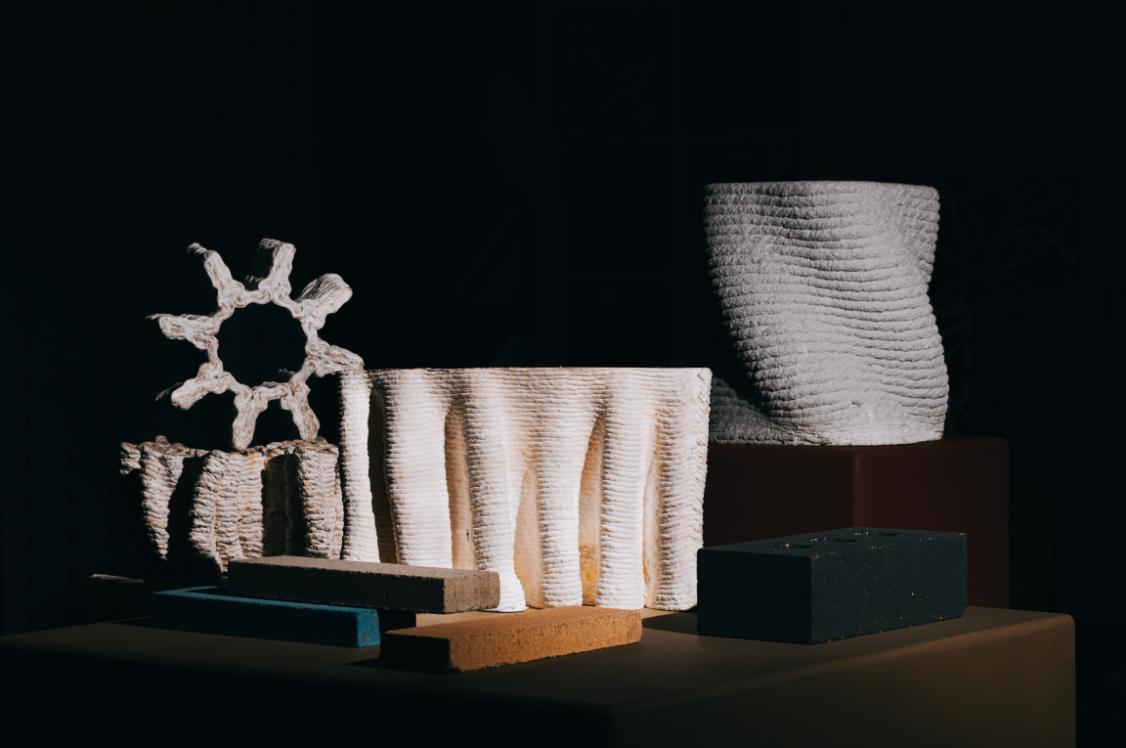

Georgie Gerrard applies a multi-disciplinary and material driven approach to her textiles practice. Using both traditional and unconventional making methods, Gerrard produced a series of grown sculptures each representing a place significant to her, as a part of her project 6 Locations. Her material of choice is mycelium - the vegetative root of a mushroom that is currently taking the biomaterials industry by storm.

Inspired by Georgie’s conceptual and geological use of mycelium, we asked her a few questions about her innovative work…

Can you please explain your project 6 Locations?

“6 Locations explores the sculptural potential of mycelium with materials relating to a specific place. Conceptually and compositionally based on Devon, Dorset, Bolton, Leicestershire and Bolivia, the resulting sculptural vessels aims to highlight the beauty and compositional versatility that mycelium can possess.

“While each location differs socially, ecologically and geologically, the material and concept are naturally intertwined.”

What was the inspiration for it?

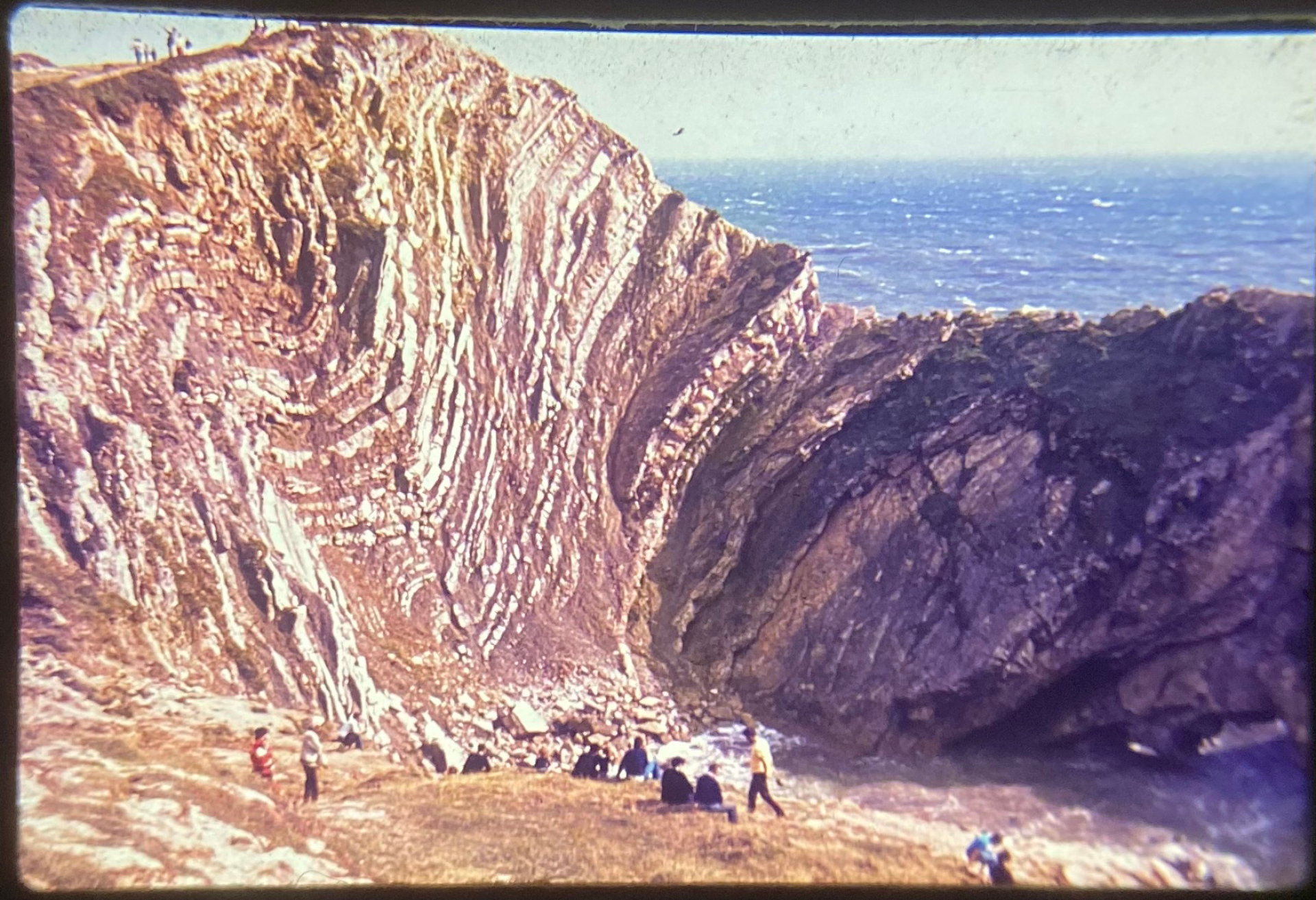

“My project is conceptually based on my ties with family located in different corners of the country and even the other side of the world. My late grandfather was a geologist. I came across hundreds of his film slides from geology field trips and family holidays, in which he relentlessly photographed geological features, rocks and fossils. The love of his subject brought me to think about how family can tie you to place.

“My project ties together the separate locations as one unified body of artefacts, reflecting the way in which they are connected by the mycelium that permeates them.”

Why was mycelium your material of choice for 6 Locations?

“I’ve grown particularly interested in working with biomaterials, due partly to the enjoyment in developing novel materials, but also their environmental benefits. They can emulate and have the potential to replace less sustainable, existing materials. Having previously worked with mycelium on an introductory level, I wanted to develop my understanding of this fascinating and hugely promising material. I did this by creating my own mycelium substrate and exploring different substrate ingredients that can be used. This was not only a personal exploration of mycelium, but also shows its aesthetic versatility in form, surface and composition.”

Obtaining materials locally reduces transport emissions, but also celebrates what we have available already around us.

The Tape Measure (1963): An image from 1963 from Georgie’s Grandfather's photo archive: a geology field trip to Dorset, featuring a tape measure and pickaxe, measuring earth layers. Shot on film.

Dorset Cliff: Film from her Grandad’s archive of geological photography

Why was obtaining local, natural materials important to your practice?

“It’s important to me to use materials that are considered, be it for the conceptual purpose of the project or because it has environmental benefits. Obtaining materials locally reduces transport emissions, but also celebrates what we have available already around us.

“With particular regard to my concept, it was important to source materials from, or related to, these individual places as I felt it was of a richer significance to the pieces. Without them, relating the pieces to the locations solely aesthetically, I felt would risk being superficial.”

I think we’re on the cusp of some really exciting developments in materials, which will ultimately re-shape the ways we live and how we interact.

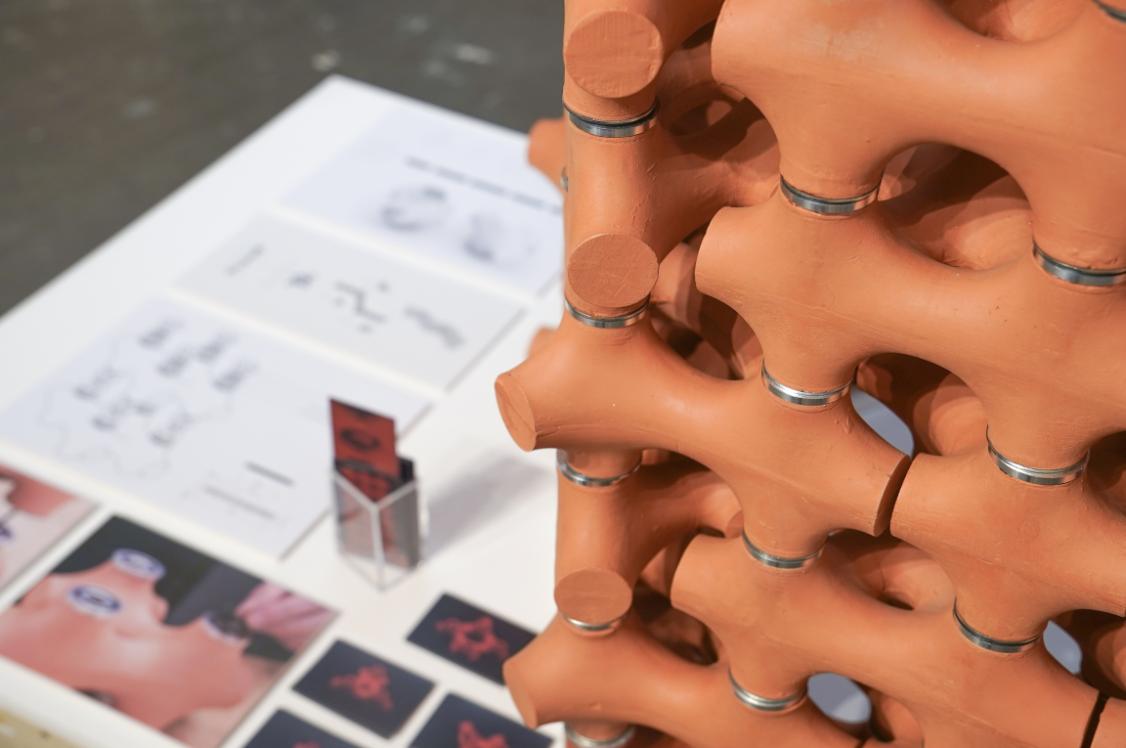

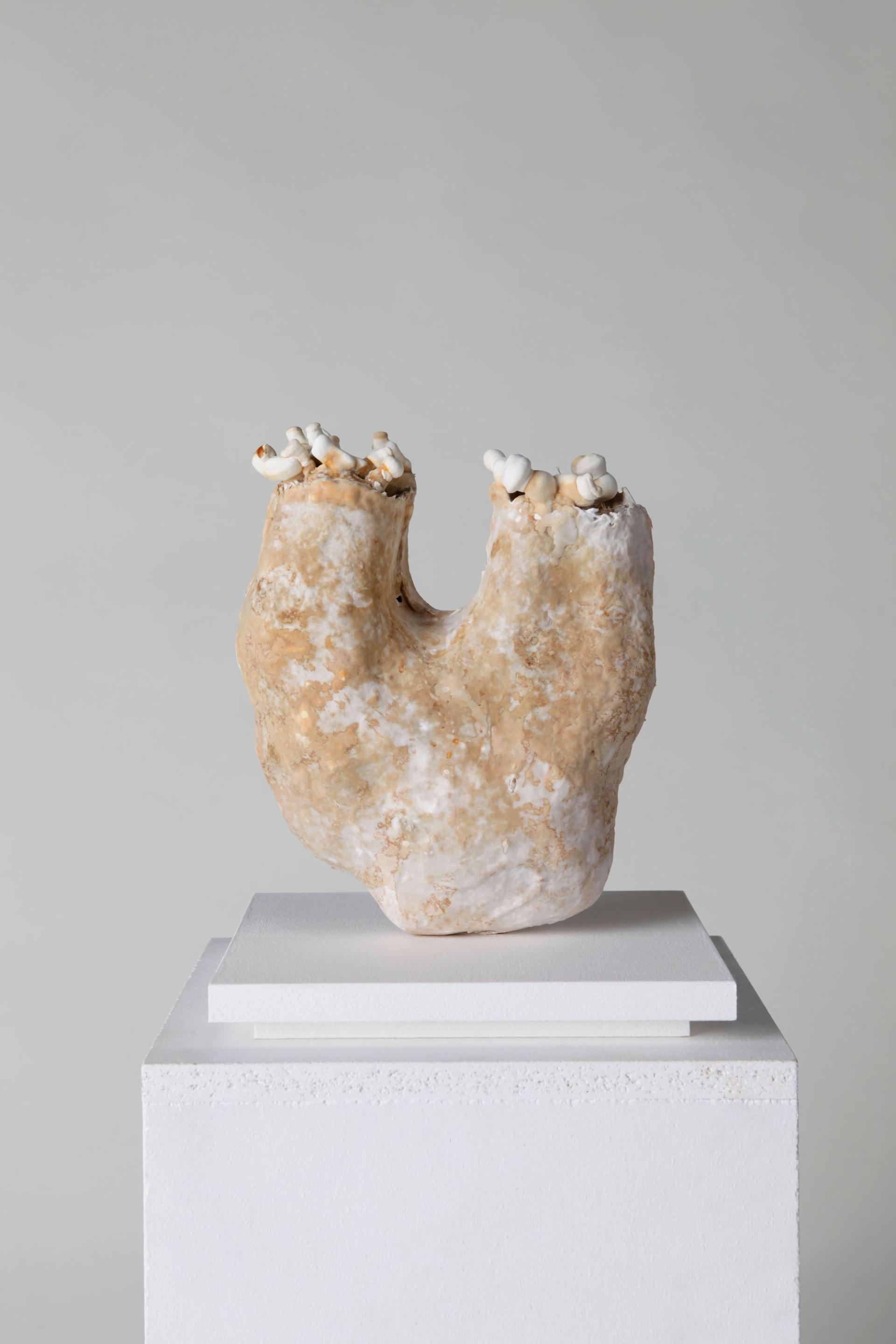

Surrey: Mycelium sculpture grown from reishi millet grain spawn, eucalyptus paper, wheat bran, and yellow clay dug up from Cranleigh, in Surrey.

How did you become interested in slow process, biologically-driven making?

“As the negative impact the design and textile industry has on our planet is becoming increasingly apparent, it didn’t make sense to me to design in a way that didn’t consider materials and process. As long as I can remember, I have been intrigued with how things are made, rather than focussing on the aesthetic of the finished product. My natural inclination to create in this way led me to the field of bio-design and working with biomaterials; particularly mycelium.

“Researching into future material concepts and biologically-driven making really opened my eyes to their potential. I think we’re on the cusp of some really exciting developments in materials for construction, architecture, interiors and fashion; which will ultimately re-shape the ways we live and how we interact with materials around us.

“I wanted to be a part of this development, and hopefully by creating these pieces, will encourage others to feel they can do the same.”

Dorset: Durdle Door: Mycelium sculpture based on the geologically fascinating Durdle Door on the south coast of England, grown from reishi oat seed spawn with barley straw, eucalyptus paper, wheat bran, and clay.

To view more of Georgie’s exciting bio developments, follow @gk.g_design.