Jon Humphreys, creative director & co-owner, Sheila Bird, on soulful placemaking - community, collaboration and a sense of pride.

Credit: Josh Kemp Smith

At one of our recent seminars, Jon Humphreys, creative director & co-owner, Sheila Bird, and I were chatting about what makes an amazing 'place'.

"It's a combination of things", Jon said. "It's when you go somewhere and love it but you might not even be sure why." I agreed. It's exactly that. But how, as built environment professionals, do you create that, without it feeling forced? "There's an article in this..." replied Jon. So we put our thoughts to paper...

The result is this week's interview, where we delve further into the topic of placemaking, to consider what it means, who needs to be involved to make it work, and whether there's a secret recipe to success.

Jon shares some of his favourite projects from the Sheila Bird team, while suggesting the places he feels have got it right. Some who've turned it around. And some of those that haven't.

We hope you enjoy the chat as much as we did. Let us know your thoughts on crafting sustainable placemaking with longevity. What should be in that coveted secret sauce?

What does placemaking mean to you/Sheila Bird?

“I think the term "placemaking" can be difficult to pin down because it is a complex field that means different things to different people. For me, it's the glue that binds together the various disparate elements that make up our built environment. Its goal is to bring places to life, give them soul and vibrancy, and create meaningful experiences. It is the thread that holds the tapestry together, so to speak.

“Placemaking is an attempt to understand what "sense of place" really means. It involves exploring how the physical, cultural, historical, and emotional perceptions of a place can be used to inform a collaborative design and activation process. One that engages people and creates a clear identity. When it’s done well, it can deepen emotional ties, increase our sense of belonging, and makes us proud.”

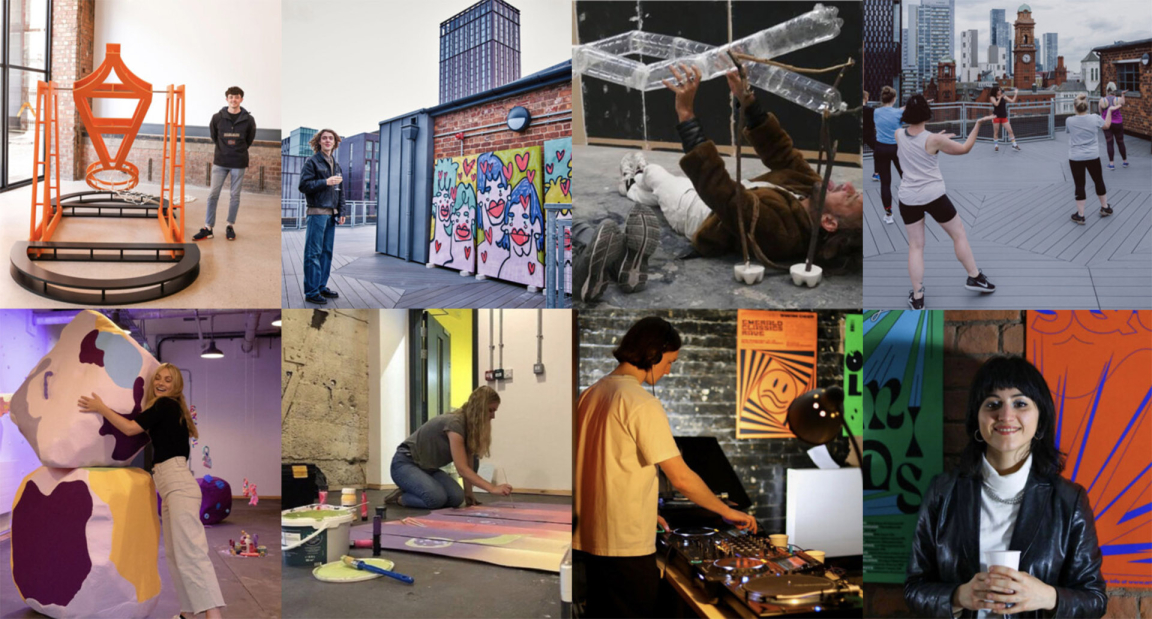

24 Lever Street - Credit: True North - Used courtesy of Sheila Bird

How does the consideration of it factor into your projects?

“Over the years, my work has been focused on two passions: brand identity and place storytelling, and designing physical spaces for communities. Both demand a deep understanding of the bond between people and place, and what people cherish and want from their environments.

“At Sheila Bird, while our design work focuses on interiors, our approach always considers the bigger picture, how spaces connect to the building, the surrounding landscape, and the life within. I’ve always loved the phrase “from district to doorknob,” shared by my friends at Hawkins\Brown, because every scale in between shapes our experience of place.

“Our work on Hilton House in the Northern Quarter was about creating the right context for community to thrive, leading to the Feel Good Club taking the ground floor. It’s now a defining part of the building’s identity and feels perfectly at home in the Northern Quarter.

“Similarly, at 24 Lever Street and 86 Princess Street, our approach is about honouring each building’s authentic fabric - both rich with original features that deserve to be celebrated, while also shaping the culture we hope to encourage. It’s about setting a vision that attracts like-minded people and builds strong, vibrant communities.

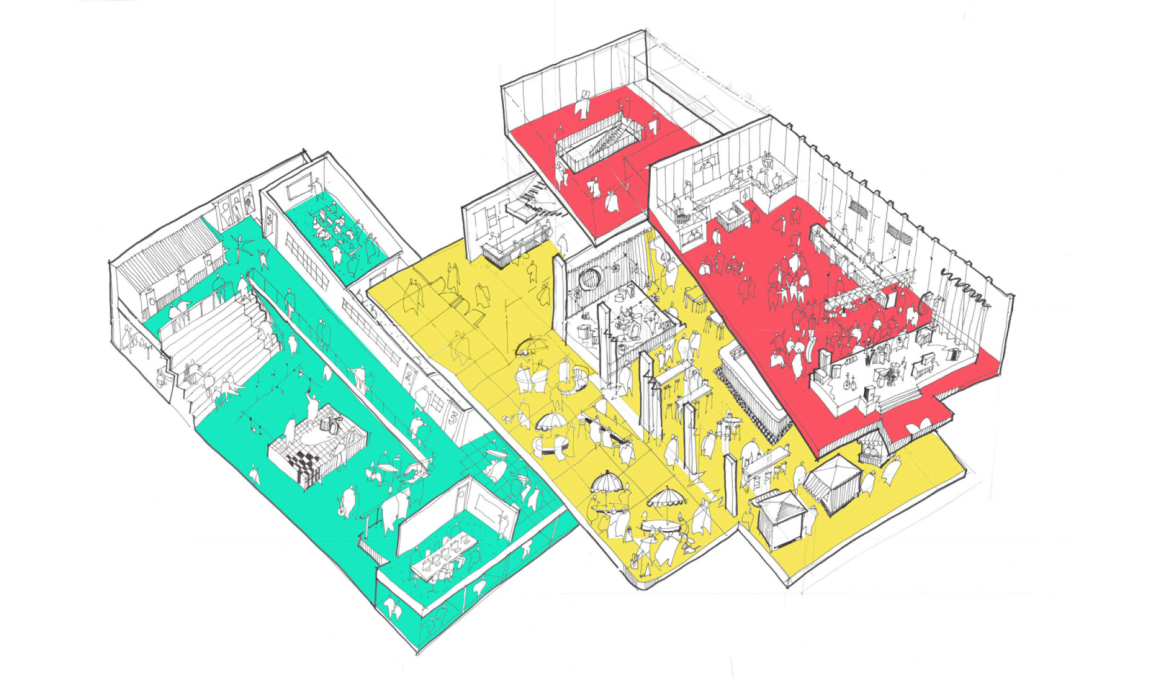

“New Century is another story of placemaking driven by passion—reviving a mothballed building and bringing it back to life. As both co-developer and designer, we focused on creating a sustainable ecosystem of connected spaces with a clear, compelling identity. From curated events and entertainment (hall) to hospitality (kitchen) and learning (college), these overlapping spaces form something greater than the sum of their parts.”

Which other stakeholders are usually also involved in placemaking?

“There can be a lot of stakeholders involved depending on the project scale. Large-scale urban placemaking projects can be complex, and the careful alignment of the different interests and perspectives can be time consuming to negotiate and manage, e.g. local government and planning departments, land owners, urban planners, landscape architects, developers, local businesses, community organisations, local residents, public safety professionals, marketing agencies, cultural organisations...the list goes on.

“The success of a placemaking project hinges on good collaboration amongst all these stakeholders. Shared goals, respect for each others' expertise and interests is essential for creating spaces that are functional, culturally relevant, and sustainable. You can’t please everyone all of the time, but striving for common goals gives the process a chance.”

Cultural activations at 86 Princess St - Credit: SeeSaw - Used courtesy of Sheila Bird

What is the ideal recipe for good placemaking?

“The recipe changes with the context of each project. But some common ingredients remain consistent for most placemaking projects. I think that these principles apply as much to the work we do in interiors as they do to large urban public spaces.

“At the core there needs to be permission and a sense of openness and ownership. People need to feel like spaces are inclusive and that they have a right to be there. The process starts with listening. A space only works if it reflects the people who use it, so engaging with the community, residents, businesses, and visitors is the first step. Their needs, ideas and feedback shape a place that feels authentic and welcoming.

“Next, it has to be for everyone. A well-designed space considers all ages and abilities, with accessible circulation, clear signage, comfortable seating, and thoughtful details that make people feel at ease. If a place isn’t easy to navigate or doesn’t feel inviting, people won’t stay. Spaces should feel comfortable, with seating arranged for conversation, cosy nooks within larger areas, and natural elements like plants and shade to create a sense of calm. A vast, empty plaza might look impressive, but if it lacks warmth, it won’t attract people.

“A strong sense of identity makes a space memorable. Using local materials, showcasing community history, and incorporating public art all help create a place that feels rooted rather than generic. When people see themselves reflected in a space, they feel a sense of ownership and pride.

“A space that regularly hosts events and supports local businesses feels authentic and lively. Giving the community a role in organising activities keeps the energy fresh and relevant. Flexibility is essential. A space that can adapt and change over time and supports different activities stays relevant and useful.

“Playfulness and creativity bring a space to life. Public art, interactive installations, elements that surprise and delight. The most-loved places have an element of fun and discovery.

“And of course, people only gather where they feel safe and comfortable. Good lighting, clear sight-lines, and well-maintained facilities encourage people to linger. A clean, well-cared-for space sends the message that it’s valued—and that makes people want to spend time there.

“Connecting with nature inside and outside is more important than ever in man-made environments. Greenery, trees, and even small garden spaces make urban environments feel more welcoming, less stressful, and healthier. All of these thoughts can influence the design of a piece of landscaping or a new workspace for a business. The principles are transferable.

"At the end of the day, the secret to placemaking isn’t just good design, it’s ongoing care, attention and evolution.

"The best places aren’t static; they grow and adapt with the people who use them.”

“A process of continuing to listen, experiment, iterate and refine creates spaces that have an active life in the future.”

When have you seen it go wrong?

“It can quite easily go wrong given all that complexity. Good placemaking is hard and isn’t a one-shot fix. Anyone can throw a good party, but keeping the energy going over a period of time is tricky. Everything from a lack of vision, collaboration, maintenance, and ongoing stewardship can scupper the most well intentioned efforts.

“A common failure is over-commercialisation and gentrification. Where commercial interests overshadow community needs, this tips the balance towards a place feeling corporate, exclusive and lacking in local ownership. It’s a fine balancing act of economics needed for viability, and genuine inclusivity.

“Some people feel like that about Granary Square in King’s Cross which is often cited as an exemplar of great public space design. Luxury commercial offerings and high levels of surveillance have made some local residents vocal about there being little sense of community ownership or local independent offerings in its DNA.”

New Century - concept sketches

And once a place lacks vibrancy, can it turn things around?

“Yes, of course, if the reason for its failure is thoroughly understood and acted upon. I mean, look at Spinningfields in Manchester. When that arrived, people likened it to Canary Wharf, soul-less, corporate glass boxes that looked as though they were dropped in from space. It was also positioned as a corporate and high-end retail destination, which was the wrong offer in the wrong place. It didn’t offer people enough reasons to visit and dwell, which gives a place life and energy.

“But, it has turned itself around. 20 years on and the edges have softened, the quality of public realm has improved, there are places to hang out, eat and drink, more reasons to linger.”

Is there a lot of red tape to deal with when it comes to designing ‘place’?

“Oh yes, there can be. Placemaking in urban spaces is not always for the faint hearted. It can be a long, arduous ride with many hurdles. Bureaucratic red tape can slow things down or force a complete rethink.

“Firstly, there’s planning permission, strict rules, months of applications, consultations, and paperwork. If the site has historical significance, things get even tougher. There are assessments, approvals, and expert input needed to make sure there’s no harm to cultural heritage. Environmental regulations can also stall progress, especially if wildlife is involved.

“Public consultations, while important, can drag out timelines. If there’s opposition, there are revisions and compromises to satisfy the community. Then there are safety and accessibility regulations, each demanding inspections, and approvals. Land ownership issues can be another snag, especially with multiple stakeholders or rights of way to navigate.

“Funding can be another hurdle, as sometimes projects rely on government grants, which come with lengthy application processes and strict oversight. Even after securing funds, maintenance costs add another layer of bureaucracy.

“Security concerns also play a role. Large gatherings might require coordination with local police, surveillance, or barriers. Noise restrictions can limit events, and in urban centres, anti-terrorism measures may be required, adding yet another layer of approvals.

“So, placemaking demands patience, flexibility, and a willingness to tackle the red tape.”

Campfield

How does design encourage places to thrive?

“If people thrive, the place thrives. Great design serves people by creating spaces they genuinely want to be in, places that make them feel good about themselves, welcomed, and connected to each other. It creates energy, sparks connections, and encourages people to fall in love with their surroundings.

“Designing thoughtful amenities and stimulating environments invites people to linger, connect, and enjoy each other’s company, resulting in a vibrant, lively atmosphere. It’s about getting the fundamentals I mentioned earlier right, accessibility, comfort, and human scale - while infusing playfulness, fun, unexpected touches, and connections to nature. These elements satisfy both our functional and emotional needs.

"It really is about permission and inclusivity, the best places remove barriers to activity.”

“When it’s easy to host an event, gather, or simply hang out, spaces stay active and loved. Thoughtful design isn’t just about aesthetics; it’s about creating places where people want to linger, connect, and return again and again.”

How does Sheila Bird factor community engagement into its projects?

“Quite simply, we talk to lots of people. We ask them many questions, engage in genuine discussion and listen. This is not about designing by committee, but about recognising that much of our role as designers of spaces is to be collaborators and facilitators, not authors. People are the authors of their own spaces. Of course, in any diverse community, it is impossible to give everyone exactly what they want. However, with careful listening, it is possible to identify common themes and shared human needs that can be integrated into the design process.

“A quote that has always stuck with me is by the artist Brian Eno. He once said that to design for life, you have to think more like a gardener and less like an architect. Design beginnings, not endings. I love this because it reminds us not to over-design. It is about leaving space in the process for others to inhabit - like planting seeds. You create the context for interesting things to happen and grow in unexpected ways. It is about designing without ego and giving a community permission and ownership of its own development.”

Art Park

You’re based in Manchester - a city with distinct neighbourhoods, such as Spinningfields and the Northern Quarter, which you mentioned. How’s it faring generally when it comes to placemaking? Are some areas doing better than others?

“Manchester is expanding at a rapid rate, offering a wealth of neighbourhoods to choose from. However, some stand out as exemplars of good design, strong identity, and long-term thinking, where a sense of purpose and stewardship is evident.

“One area that has always made an impression on me from an early age, as a visiting Scouser, is Castlefield. Arriving via the elevated railway line, overlooking brick warehouses, bridges, and canals, was - and still is - a dramatic experience unlike anything I had seen in Liverpool. In a certain light, it felt like a film set - almost like Gotham - very industrial, yet with a strong sense of character and identity.

“As one of the first neighbourhoods in the city centre to undergo conservation and regeneration, Castlefield has had time to mature. Forty years on, it is still evolving. The drama is now heightened by the backdrop of huge, futuristic glass towers. But perhaps even more interesting is how it is merging with St John’s, Factory International, and Enterprise City. We have been involved in the design and development of the Campfield Buildings, the former Air and Space Museum - a true treasure of Manchester’s heritage, that will now become part of its future for a new generation to enjoy.

“I think Kampus is good example of successful placemaking at a hyperlocal, neighbourhood level. It is a lovely little oasis with well-executed public spaces, a diverse mix of uses, and varied building characters. I was involved with this project about 12 years ago, helping Capital & Centric shape and communicate the vision long before any development took place. It is wonderful to see it delivered so well.

“Of course, NOMA also deserves mention as another strong example. While still in its early stages, it is slowly developing as its community and footfall grow. Once considered on the fringe of the city, it will soon feel much more central. This area is rooted in strong principles and community stewardship, embodied by the landscaping and community placemaking initiatives by Planit/Standard Practice. The reactivation of characterful heritage buildings, from Victorian gems like Hanover to Modernist landmarks such as our project at New Century, is creating more reasons for people to live, work, and socialise here.

“I love the fact that you guys at Material Source are very integral to this neighbourhood, always offering a warm welcome to everyone and committed to building a real community around the things you do.

“One of my favourite new additions to the area is Altogether Otherwise, a space for people to come together and pursue their hobbies. It is a fantastic example of a shared ethos and creative neighbourhood thinking.”

Stopford Community - Credit: Madeline Penfold

What are you currently working on?

“We are currently working on a placemaking project in Stockport, creating a new mixed-use neighbourhood that blends old and new buildings in the town centre. Our role is interesting because we are considering everything from the macro to the micro scale.

“One aspect of our work is defining the overall place narrative and identity, from its name and core values to its visual language. This, in turn, has influenced the broader purpose and design of the spaces, including the landscaping, which will now become a small curated "art park” with an additional layer of purpose and connection to its locality beyond being a residents’ garden. Creating a dialogue with the local community from day one is important, the hoarding campaign we created around the site involves and celebrates the people in Stockport who are actively making a difference in the town.

“On a more detailed level, we are also designing the interior spaces in the buildings on the site, from co-working studios in a Grade II listed building to residential and amenity areas in newly built structures. It is a true journey joining the dots between "district and doorknob”, exactly the kind of project we love.”