The Spaces for Wellbeing design collective on biotechnologies in interiors, sensory experience, and what constitutes a truly restorative space.

Continuing our editorial focus on the complex yet crucial topic of designing for EDI is an interview with the creative collective behind Spaces for Wellbeing.

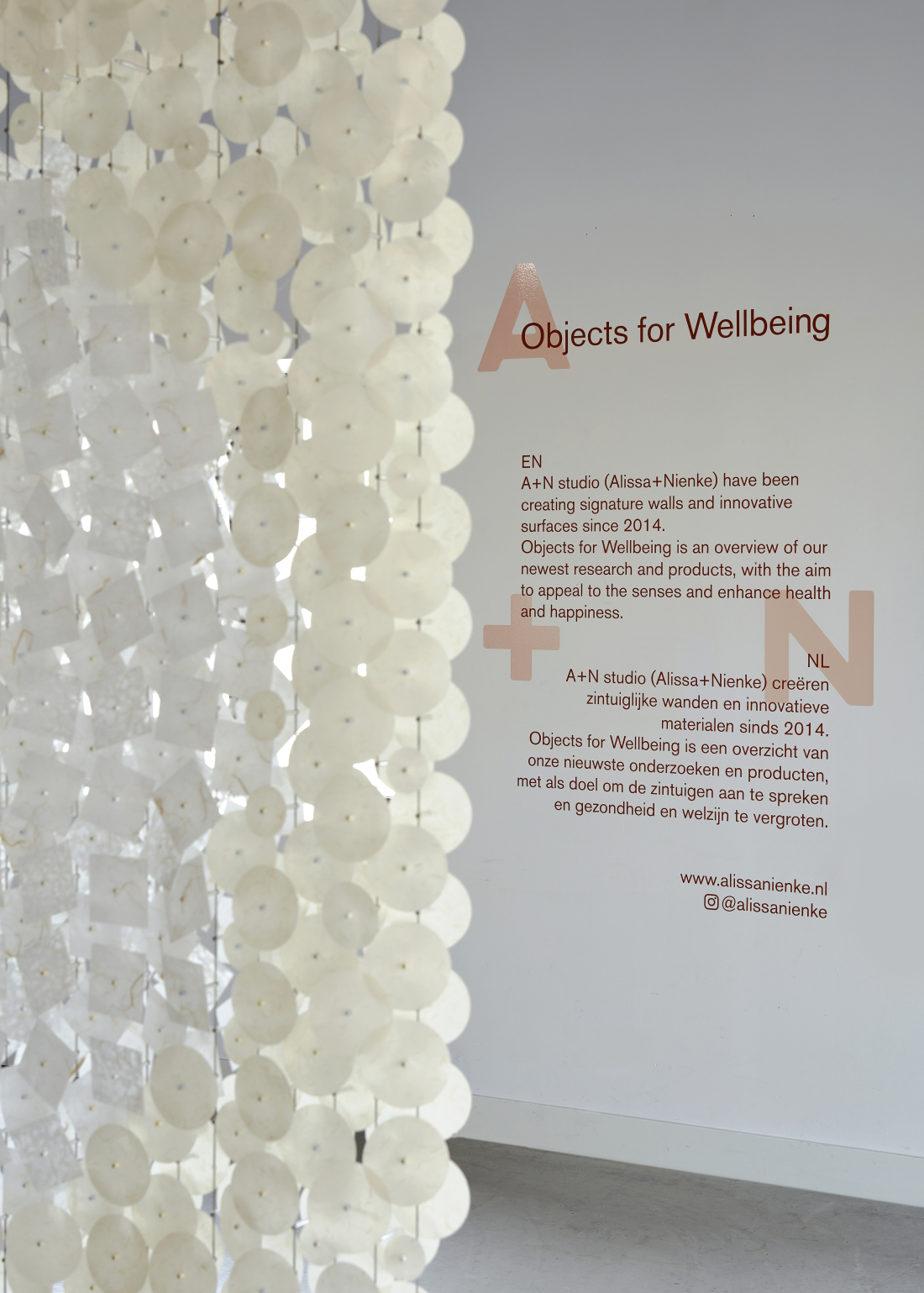

Alissa van Asseldonk and Nienke Bongers are the cofounders of A+N Studio, an Eindhoven-based material research and design practice crafting innovative objects and surfaces for ‘future’ interior architecture. Together, they have joined forces with Renske Bongers, an environmental psychologist at Senses & Spaces, and Justine Kontou, sensorial curator at Studio Kontou, to form the Spaces for Wellbeing design collective.

Fostering the prevalent connection between human psychology, material design and spacial design, the team creates research and evidence based spaces using sensory experience as a tool to influence mood. Within these spaces, materials feature based on sensory information processing and behavioural research, creating a holistically harmonious experience for users.

Drawing on parallels discussed at our MSS Presents: Designing for EDI seminar with founder of Soyo Ltd and author of Reworked, Dr Stephanie Fitzgerald, we chatted with Nienke, Renske and Justine about the problems of modern day office plans, such as privacy, territorial behaviour and the lack of control offered over peoples' surrounding environment, as well as the importance of uncovering both the conscious and subconscious needs of people within a space.

We also discuss the research behind what constitutes a truly restorative space, the benefits of implementing both Attention Restoration Theory - a concept based on natural phenomena - and biofeedback technologies into interior materials. As well as the importance of truly understanding biophilia in order to incorporate it effectively within the environments we inhabit.

NB: Nienke Bongers: designer at A+N Studio (Alissa+Nienke)

RB: Renske Bongers: environmental psychologist - Senses & Spaces

JK: Justine Kontou: sensorial curator - Studio Kontou

Spaces for Wellbeing. Photography by Ronald Smit

Firstly, could you please introduce us to your collaborative project, Spaces for Wellbeing?

NB: “Spaces for Wellbeing (SfWB) is a collective of designers including; Alissa van Asseldonk and Nienke Bongers of A+N Studio, environmental psychologist, Renske Bongers and sensorial curator, Justine Kontou of Studio Kontou. Within A+N Studio, we started collaborating with Renske about five years ago in order to add behavioural research to our work. This was to enhance the impact of our materials and installations on wellbeing and also to use psychological theories as a new perspective and an inspiration to design from.

“For Renske, this collaboration meant taking psychological interventions in the physical environment to the next level. To use the designers' mind to create interventions in the physical environment showed her a whole new dimension of possibilities - a win win situation!

“Together, we extended this collaboration with Justine, who has an eye for the surrounding environment as a whole, using sensory experience as a default. With her eye for detail, we can design spaces as an entirety. It made sense to combine these disciplines into a collaboration, and Spaces for Wellbeing was created.”

RB: “We all believe that the physical environment has way more of an impact on us than we can imagine. Everywhere we are, information is coming in. And with the fast paced society we live in, this is often draining energy from us. We believe this can be different. A space can also contribute to health and happiness, making us feel well within ourselves and energised.

“Because of the powerful impact our environment can have on us, we want to create research and evidence based spaces - using the sensory experience as a tool to influence your mood. Since all of us have different disciplines, we are able to contribute on different levels. This can be researching behaviour, designing materials, objects and installations, and designing a space as an entirety.”

Spaces for Wellbeing. Photography by Ronald Smit

Spaces for Wellbeing. Photography by Ronald Smit

What steps should a designer first undertake in order to create meaningful, healthy spaces for a neurodivergent community?

RB: “Firstly, get to know your target audience. Especially when you are designing for health and wellbeing. Know who you are designing for, how they behave and function and what they need – both on a conscious and subconscious level. See if you can dig a tiny bit deeper than asking what they need. Working with a behavioural scientist or psychologist can give you more insights and design criteria to use.”

NB: “Then you can start designing in an intuitive way with this input in mind. Usually in the design process, we build in a couple of moments to reflect on where we are and if we’re still close to the needs of the audience. We look at how the designs work and whether there needs to be any changes made. This exchange helps the design process if we focus on a specific target audience.”

How do you select your materials for your site-specific installations?

NB: “This also depends on the target group and context. Our client typically gives criteria on what materials they feel are suited. For example, when you're working for an educational setting, everything has to be resistant against vandalism. The material should not be fragile and easy to break. Within a hospital, hygiene is very important, so you need to be able to easily clean it, using perhaps harsh chemicals and fluids on it every single day.

“Next to the practical decisions, there is the more intuitive way of looking at materials. Here we query the feeling we want to create for our clients, focusing on questions like: Does it need to look soft and rounded, would we like to work with a lot of small details or with reflection?”

JK: “After we have a clear view of the desired state of mind of the users within the space, we make a bespoke concept and design for site specific installations whilst enhancing spatial elements to surround it with. This all contributes to stimulating that desired state of mind.

“Among other things, we apply biophilic design principles. Biophilia suggests that humans have an innate tendency to seek connections with nature and other forms of life and biophilic design presumes that by integrating natural elements in the built environment this can reduce stress, improve well-being and is linked to faster healing. This goes way beyond integrating plants into a space, and is also about creating soft boundaries, using natural materials, a diversity of textures and sensory stimuli and offering a variety of ‘natural landscapes’ in a building. For example, places where you can retreat and places that gives you a clear overview and lookout.

“When we select materials we keep the experience of these materials in mind; what kind of texture does it have, how does it feel, what colour does it have and can its appearance change from different perspectives? Alongside the visual elements of a space, other stimuli is of equal importance. Textures, scents and sounds are three other elements we prefer to include in the entire space. We take into account the complete sensory experience, and with all the different elements, we compose one harmonious spatial setting.”

Spaces for Wellbeing. Photography by Ronald Smit

You mention healing - how does your work apply to the healthcare sector?

RB: “The difference with a healthcare environment is that the patients and visitors coming in often have to deal with a lot of uncertainty and insecurities, which is already generating a baseline of physiological and mental stress. This often results in a reduced capacity of dealing with the information being received.

“When we are in a hospital, a lot of information is coming in and needs to be processed and reacted to. There are steps to take when signing in, finding your way to the right department, when you are visiting a doctor you have to listen and understand a lot of medical jargon. All these things add up and can result in an information overload - both on a sensory level and a conscious level.

“When you are admitted to a hospital, noise especially can have a negative impact. There is the noise of people talking around you, machines beeping, IV alarms going off. And when rest is needed to heal, it can be hard to do this with all these sounds around you.

“A lack of privacy is the next aspect which can negatively impact. Often patients have to share a room, medical staff are walking in and out, or doors stay open during the day. Having to discuss personal subject matters with a neighbouring patient lying next to you can be difficult.

“Finally - although it is slowly changing - hospitals tend to be white, sterile environments with a lack of positive distractions. There is psychological research to support that this kind of under stimulating environment can negatively impact on a patients' mental and physiological health. Making the environment warmer and more approachable can alter this experience. These positive distractions not only allow patients to pass the time, but help to distract them from feeling pain in their body, by focusing on something outside of themselves. When done well, it can even result in using less pain medication.”

JK: “In addition, many visitors - both patients and their guests - experience hospitals as cold, sterile spaces, in which they feel everything but ease. This can result in more stress and anxiety. By creating an environment that feels warm, inviting and safe, it is easier to relax and this can benefit the healing process of the patient.”

A truly restorative space is based on the people using it, how they behave and what they consciously or subconsciously need - Renske Bongers

Where do you source inspiration for the surface design qualities of your interior artworks?

NB: “Inspiration is everywhere around us. We find it in the outdoors, in the city, looking at buildings, and also in nature. Seeing repetitive patterns, organic shapes or movements - like a flock of birds. We also look to art, culture and design in galleries, museums or online.”

JK: “For me personally, nature and more specifically the wonder sunlight creates while it shines through the trees is where I gain a lot of inspiration. It creates the most interesting shadowplay, when it twinkles on the water or when you see the sun rays shining from behind a cloud. Over and over again, this takes my breath away and creates a lot of inspiration. As well as all the different textures you can find in our natural surroundings.”

Tell us more about your recent project with the Woodward Hotel in Geneva?

NB: “Comet is a bespoke installation we created for the Woodward Hotel in Geneva in 2021. This masterpiece came together in a perfect collaboration with the team at Atelier 27. More than 1,500 individual shapes - slowly moved by the wind and reflecting light - form the floating heart of the hotel, surprising you in the entrance hall. It’s an installation that surprises you from every angle."

Spaces for Wellbeing. Photography by Ronald Smit

Neurodiversity spans a wide spectrum of different people with a range of different needs. How do you design for all definitions of a healthy, enriching environment?

RB: “Ideally you would design an environment helping different kinds of people all at once. In which you can ask yourself the question: Do they all need to function in the same space or do we need to create different spaces for different needs? Or, if we create one space, how can we make it adaptable to different needs?

“To get to this point, I believe, is a long term process. Not only is there still much to learn about neurodiversity itself, also steps need to be made in creating new norms about neurodiversity. Making it the norm itself that everyone is diverse and has different needs in different moments. Accepting that people - who, for example, are more sensitive - are not a minority, but a group of people that need to take more time to recharge their battery, or sit in a more quiet space every now and then.

“To get there we need to take small steps. You focus on one or two types of people. For example, people that are easily overstimulated and/or people that need to release energy. Everytime we design and research something, we learn. Every bit we learn, we can use in a project or translate to the next target group. By working context-specific, we need to dive into the target group that is there and adapt our design to what they need. Due to this way of working, we meet different types of people. At some point in the future, we’ll get better and better in combining a range of different needs, resulting in a healthy environment for everyone.”

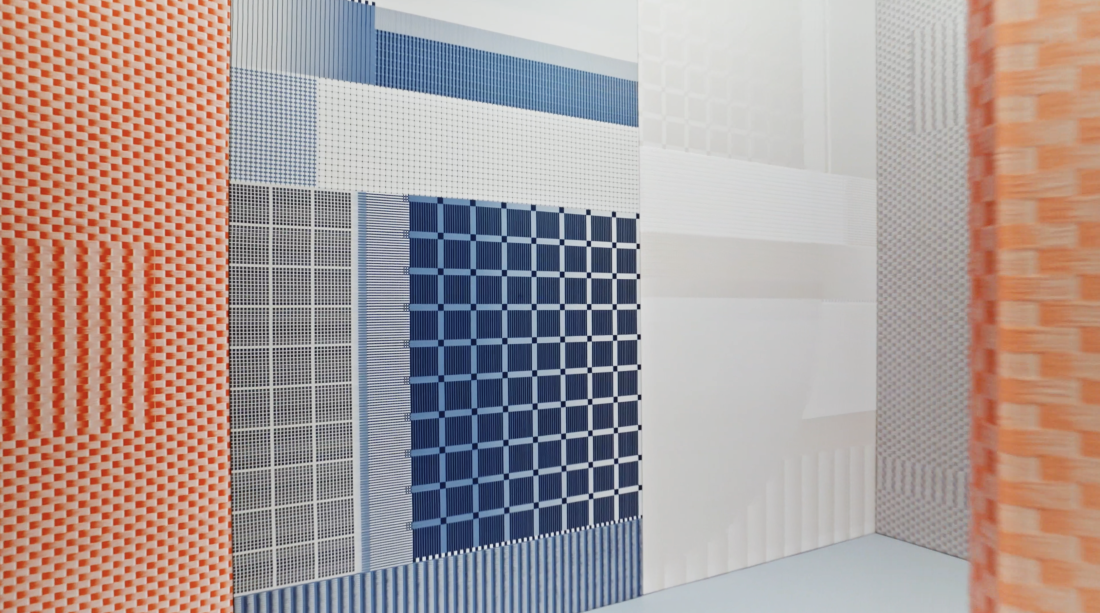

Spaces for Wellbeing. Photography by Ronald Smit

Could you please explain the design thinking behind the colour palette of Spaces for Wellbeing. Does an understanding of colour psychology play a part?

NB: “For the Spaces for Wellbeing exhibition, we selected colours based on certain textures and patterns we had already created. The aim was to influence the audience to experience three different ‘moods’; focus, relaxation and activation. We didn’t develop new designs for the exhibition but combined existing ones in a certain way to create these moods. We chose them with Renske’s input about human behaviour and what felt intuitive to us.”

When we select materials, we keep the experience of these materials in mind - Justine Kontou

What do haptic, sensory stimulating walls positively promote for the inhabitants of a space?

RB: “Again, depending on the target audience, it has the potential to promote different outcomes. When we implemented a haptic, multi sensory wall in a healthcare facility for an elderly group of people with diverse needs, it was done so with the intention of helping these people to feel calm. Touch and haptic stimulation is a very direct way of being in touch with our body. It gets us away from our train of thought and into the here and now of experiencing. This is often a quick way to relax the mind and reduce stress.

“But in a different context - for example, a work environment - it could be used as a means to get people out of their sense of normality and enhance creativity. By using different senses, different areas of the brain are stimulated. Activating neural connections that can be used during a creative process and has the potential to generate more ideas.”

Could you talk us through some of the research you have undertaken to understand how physical environments impact a person's state of mind?

RB: “Over the past five years, we have completed several projects all based on designing and researching the impact of materials and installations applied within a particular space. We gather data during the development of new objects or installations to inform our next designs. At the base of these developments lies the idea of sensory information processing. We question which information from the physical environment is coming in and how this impacts users of the space. When we apply objects in a space, we start by diving into the context of this space: Who is there? What is happening? How are they behaving and feeling? Which sensory information is coming in and how does this have an impact? What needs to change?

“We are currently researching a department in a hospital that gives day treatment to patients with cancer. By diving into this context, we have learnt several things. For example, noise is having a negative impact on patients. Hearing people talk in the hallway, machines beeping and alarms going off. The patients can’t influence these sounds themselves, resulting in increased stress.

“By interviewing, observing, and examining academic literature, we endeavour to uncover the psychological factors negatively impacting people’s experiences within the space. Based on these findings, we are now designing a space for wellbeing in this department, in which we will later on research its impact. The question is: How can the physical environment enhance the feeling of social support and/or how can we design this?

“Another example would be, not researching a physical environment itself, but using psychological concepts based on environmental awareness to enhance wellbeing. Attention Restoration Theory is one of my favourites. It’s based on natural phenomena; like wind going through the leaves, water ripples or clouds passing by. These kinds of nature-based phenomena instil a soft fascination in people, both effortless and soothing to look at. By letting go of focused attention, we are able to restore our mental capacity. With the development of objects and installations, we try to translate this type of impact into the physical environment.

"Breathing Light is our newest example of this. By using dynamic light, we create slowly moving light patterns to enhance this feeling of soft fascination. Through reviewing the design both within our internal team and with the target audience, we can obtain insight on how it works and the changes that can be made. In every project we embark on, we learn. Sometimes these can be big learning curves, and sometimes they’re much smaller. But every step is one that makes our work better and better.”

Objects for Wellbeing at Dutch Design Week.

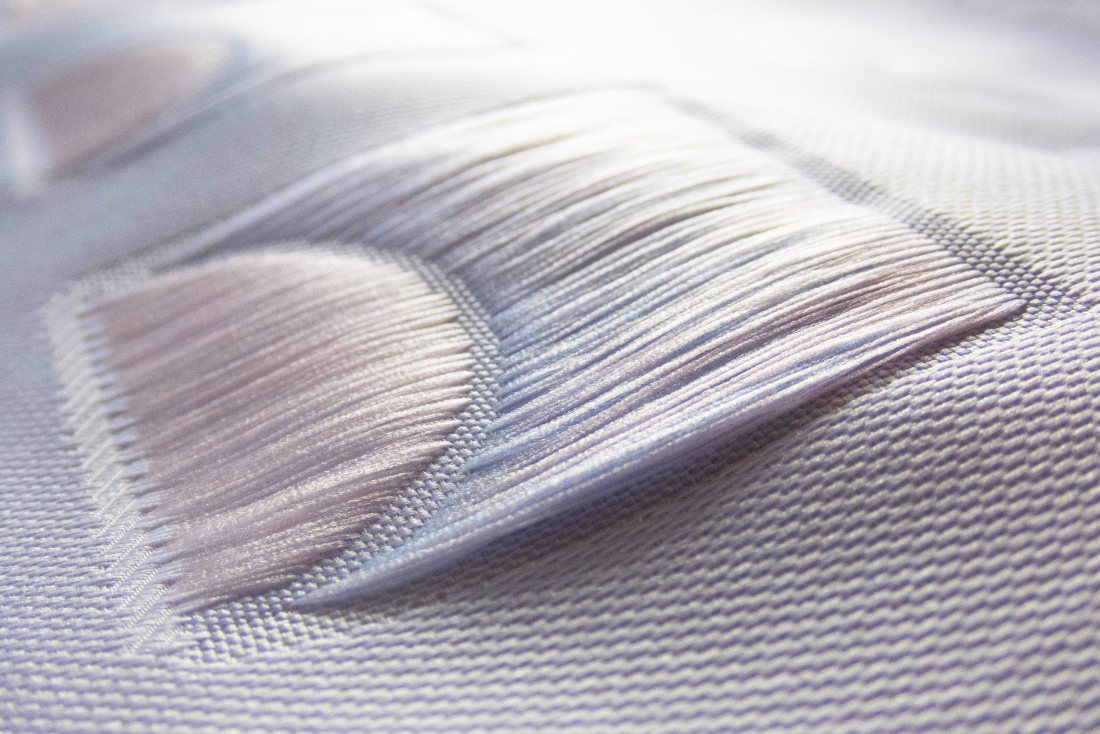

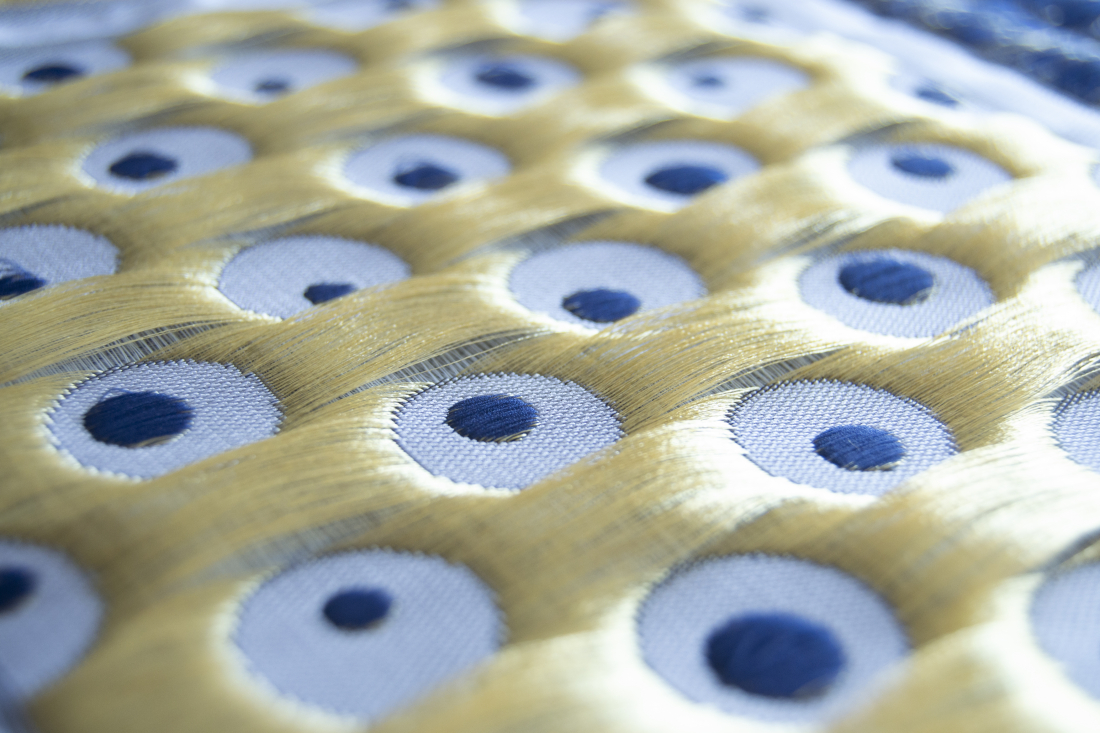

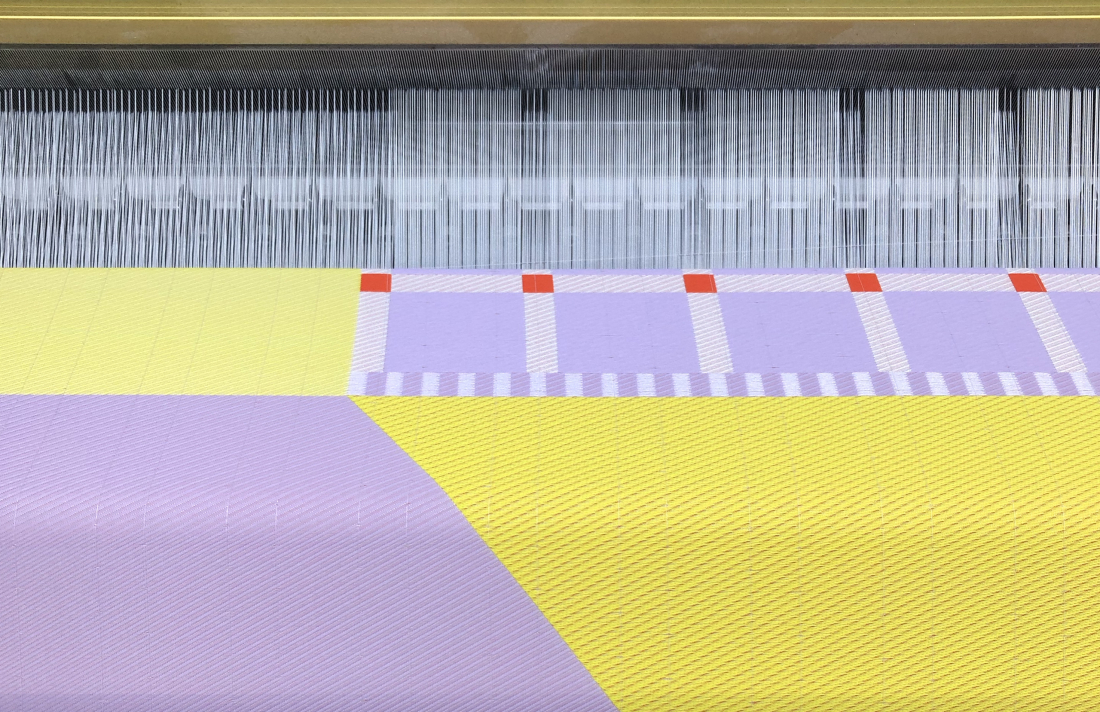

You work a lot with jacquard weaving techniques at a large scale. How does this process lend itself to creating restorative interior materials?

NB: “Textiles are a soft material, but through using Jacquard weaving techniques we can create a wide range of different textures and types of softness. We can really play with the tactility element of the material with this production technique. Textile materials typically promote feelings of softness and warmth. However, we can enhance this feeling or promote an entirely different mood altogether through applying different threads or weaving techniques - it can be used to set context.

“In addition, the production technique lends itself really well to create different kinds of patterns. With the ability to create details and layering, it can potentially stimulate soft fascination in a way. Just staring at the material, there are so many different visual queues that can be picked up. For example, in Fringes and Floats we really worked with layering in the textile, there is so much to discover through sight and tactile play. We haven’t designed it with this idea as a tool for soft fascination yet, but it definitely has the potential.”

Can you introduce us to your work with biofeedback technologies? And what are the benefits of implementing these visualisations of biological feedback into interior materials?

RB: “A+N’s research on biofeedback was the first reason I started collaborating with them. By making this biofeedback data, such as heart rate, tangible and not digital, I saw so many possibilities in how we could apply it, and what kind of impact translating this technology could make in helping reduce stress.

“With the funding of Impulsgelden Brabant, we were able to continue the development together. Ironically, we started by using VR as a research tool. This is because use of VR enabled us to get through the design process faster, making it possible to learn about the moving patterns of the ‘analogue versions’ A+N previously designed. The research is still ongoing, tackling how we can apply biological visualisations in interiors.

“Biofeedback data is typically used as a training tool, for example helping people regulate their heart rate by getting feedback on what is happening right now and what happens when you change your breathing pace. We love to explore the subconscious level of seeing this kind of data. If it’s there in the background, like a living surface, does it have an impact on our breathing pace or heart rate variability?

We like to ask questions like: Do we implement it as a feedforward system (giving a set pace) or can we make it adaptable, reacting to our data first (feedback) and helping us into a relaxing pace (feedforward). Breathing Light is an object in which we applied a feedforward relaxing breathing rhythm. Used in a conscious way (knowing there is a rhythm, choosing to follow it) we are already seeing the first signs of an improved heart rate variability, an indication it can reduce stress.”

Spaces for Wellbeing. Photography by Ronald Smit

Tell us about your recent showcase at Milan Design Week?

NB: “This year we have exhibited during Milan Design Week at the Gallery of Rossana Orlandi. We showcased a selection of the objects that focus on the wellbeing side of design, originally exhibited at Dutch Design Week 2023, Objects for Well Being. Visitors engaged with tactile wallhangings made of felted wool, kinetic artworks that respond to airflow and move like the rippling of a water surface; Dangling Mirror, and the room divider Metamorphosis: Metamorphosis is poetic and refined, enriching the everyday environment. It triggers your senses and stimulates concentration and focus, based on the Attention Restoration Theory."

Finally, how do you envision the insights behind Spaces for Wellbeing scaling into commercial interior schemes?

JK: “Currently, our ambition is to make a difference for people who need it the most. To contribute to enhancing the sense of wellbeing of those users is our main priority. Therefore, we feel very grateful to work with hospitals, health care institutions, education spaces and workplaces.

“People spend a lot of hours of the day in their workplace and educational premises. With an increasing sense of pressure, stress and a digital overload of information within these environments, it makes sense that we can make a big difference here. As Renske mentioned before, people are different and therefore also have different needs. But if we look at biophilic design principles for example, there are spatial elements that create a healthier environment for people in general. Therefore, it is possible to create interior schemes that enhance tranquility, or stimulate interactions and boost energy.”

RB: “Adding to what Justine said: The beauty of what we do is that with every project, we learn. About different contexts and different target groups, but even more about how our materials, installations and spaces work. With this learning curve, we can translate it to different target groups and make it work for that specific context. Right now, we start with custom made projects for patients and other vulnerable target groups and are looking at the value we bring. We would love to continue with this. However, the next project could also easily be an office space.

To learn more about Spaces for Wellbeing, click here